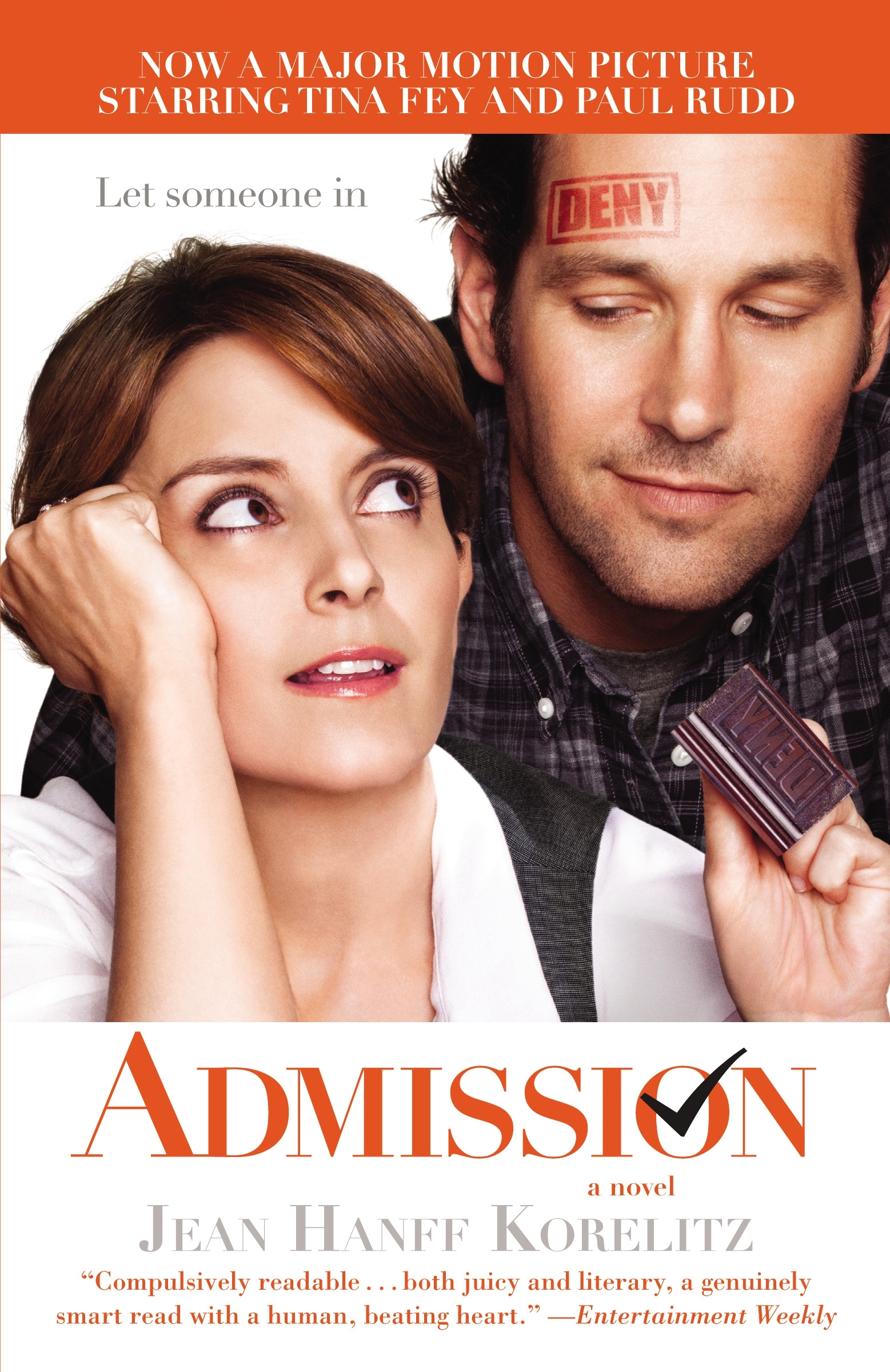

By: Jean Hanff

Korelitz

Genre: Fiction,

Drama, Romance, Self-Acceptance

“Admissions…Admission…Aren’t

there two sides to the word? And two opposing sides…It’s what we let in, but it’s

also what we let out.”

The above quote sums up the plot of this story nicely. The

story follows Portia Nathan as she struggles with the changes in her life and

confronts her past. Portia is an admissions officer for Princeton University,

and as part of her job, she travels throughout New England, visiting many

schools to recruit applicants. Upon visiting Quest, an experimental alternative

education high school, she comes face to face with John Halsey, a man from her

college years. The two spend an evening together, and upon returning home, her

world seems to fall apart. Portia is forced on a journey of admission –

admitting that her life may not be what she wants, admitting her past exists,

and admitting the right people into her life.

Portia is a realistic heroine, but I often found it hard to understand her motivations. There are occasions where I can relate to her, such as her tendency to hold onto relationships when they are no longer working and a career she doesn't really enjoy. These things are safety nets and we all have one thing we can't release, even when it's long past time to do so. However, I can't understand why she refuses to let anyone in - not her mother, who may be a bit overbearing in her radical feminism; and not her friend Rachel, who is there for her, trying to get Portia to talk to her. Portia can only seem to open up to men - to John and to Mark - never the women in her life that care so much for her.

I don't really understand why Portia and her mother have such a strained relationship. Susannah may be a bit eccentric, but her heart is in the right place, and she managed to raise Portia single-handedly. She may have some radical ideas and stick to her opinions no matter the evidence against them, but she loves Portia and wants a relationship with her - something Portia doesn't seem capable of giving to her. The two may not see eye to eye, but it's obvious that Susannah would do anything to ensure Portia's happiness. It aggravated me that Portia, at thirty-eight, was treating her mother with the disdain of a teenager.

Some of this treatment is slightly explained in Part III of the novel, when Portia admits the long-harbored secret from her past. She took care of her issue all on her own, never telling anyone because she didn't want to accept this change in her life. Even though she knew her mother would help her, she didn't want it. She gives no explanation for why, and I found it hard to understand her reasoning.

She makes a lot of decisions I do not understand - not involving her mother when her past issue arose, and the decision she made towards the end of the novel that put her career in jeopardy. Was it really worth it? I suppose, but I could never do what she did.

She also tends to go catatonic whenever a man leaves her. It's like she's in shock and doesn't know how to handle this abandonment, It happens both with her college boyfriend, Tom, as well as her live-in boyfriend of sixteen years, Mark. Her pain is certainly understandable, but she just drags herself away from the world, avoiding everyone who could help. It proves how little self-esteem she truly has and sometimes a character like that is hard to read about. I would have liked to see that she got some help for what is clearly a form of clinical depression, but sadly, that does not occur. Being so down that you let your laundry pile up, rarely bathe, hardly eat, and immerse yourself in work is terribly unhealthy, and while I was glad she was able to gradually work herself out of it, I still feel that she needs to seek professional help for it.

I do like that the book promotes a healthy romance. When she is with John their interactions are cute and respectful of one another. They laugh and tease each other, have intellectual and meaningful conversations, and don't flip out on one another for stupid reasons. She is able to be herself around him and he loves her for exactly who she is - he always has. For once, the man is waiting for the woman to decide she wants the relationship, silently pining, but not letting it consume him. Also, I like that the romance is not the central focus of the novel - Portia's character growth is. Both she and John continue their normal lives, even though something is clearly developing between them. It is a relationship I found myself rooting for because I knew that John would be good for her.

I do feel that the book suffers a lot from extensive exposition. There are many times that I found myself getting lost in thought and losing my place. Not everything needs to be given so much explanation. Let it unfold naturally. I don't need to know every last detail. There are also points of redundancy, such as in mid-conversation: "He laughed. He said, 'I'm on my way.'" Couldn't it have just been, "He laughed, 'I'm on my way.'"? I think most readers get that he is responding to her with that alone. I don't think the "he said" is necessary. Lastly, there are a few name mix-ups in the final fourth of the novel - something an editor should have caught. The rest of the novel is pristine and error free, but those name mix-ups are jarring.

Overall, it is a decent read, but I probably won't revisit it. Portia is a very real character, even if she isn't always relatable or likable. The romance is cute and understated; a simple factor in Portia's journey to self-acceptance - something she desperately needs.

6.5/10

Portia is a realistic heroine, but I often found it hard to understand her motivations. There are occasions where I can relate to her, such as her tendency to hold onto relationships when they are no longer working and a career she doesn't really enjoy. These things are safety nets and we all have one thing we can't release, even when it's long past time to do so. However, I can't understand why she refuses to let anyone in - not her mother, who may be a bit overbearing in her radical feminism; and not her friend Rachel, who is there for her, trying to get Portia to talk to her. Portia can only seem to open up to men - to John and to Mark - never the women in her life that care so much for her.

I don't really understand why Portia and her mother have such a strained relationship. Susannah may be a bit eccentric, but her heart is in the right place, and she managed to raise Portia single-handedly. She may have some radical ideas and stick to her opinions no matter the evidence against them, but she loves Portia and wants a relationship with her - something Portia doesn't seem capable of giving to her. The two may not see eye to eye, but it's obvious that Susannah would do anything to ensure Portia's happiness. It aggravated me that Portia, at thirty-eight, was treating her mother with the disdain of a teenager.

Some of this treatment is slightly explained in Part III of the novel, when Portia admits the long-harbored secret from her past. She took care of her issue all on her own, never telling anyone because she didn't want to accept this change in her life. Even though she knew her mother would help her, she didn't want it. She gives no explanation for why, and I found it hard to understand her reasoning.

She makes a lot of decisions I do not understand - not involving her mother when her past issue arose, and the decision she made towards the end of the novel that put her career in jeopardy. Was it really worth it? I suppose, but I could never do what she did.

She also tends to go catatonic whenever a man leaves her. It's like she's in shock and doesn't know how to handle this abandonment, It happens both with her college boyfriend, Tom, as well as her live-in boyfriend of sixteen years, Mark. Her pain is certainly understandable, but she just drags herself away from the world, avoiding everyone who could help. It proves how little self-esteem she truly has and sometimes a character like that is hard to read about. I would have liked to see that she got some help for what is clearly a form of clinical depression, but sadly, that does not occur. Being so down that you let your laundry pile up, rarely bathe, hardly eat, and immerse yourself in work is terribly unhealthy, and while I was glad she was able to gradually work herself out of it, I still feel that she needs to seek professional help for it.

I do like that the book promotes a healthy romance. When she is with John their interactions are cute and respectful of one another. They laugh and tease each other, have intellectual and meaningful conversations, and don't flip out on one another for stupid reasons. She is able to be herself around him and he loves her for exactly who she is - he always has. For once, the man is waiting for the woman to decide she wants the relationship, silently pining, but not letting it consume him. Also, I like that the romance is not the central focus of the novel - Portia's character growth is. Both she and John continue their normal lives, even though something is clearly developing between them. It is a relationship I found myself rooting for because I knew that John would be good for her.

I do feel that the book suffers a lot from extensive exposition. There are many times that I found myself getting lost in thought and losing my place. Not everything needs to be given so much explanation. Let it unfold naturally. I don't need to know every last detail. There are also points of redundancy, such as in mid-conversation: "He laughed. He said, 'I'm on my way.'" Couldn't it have just been, "He laughed, 'I'm on my way.'"? I think most readers get that he is responding to her with that alone. I don't think the "he said" is necessary. Lastly, there are a few name mix-ups in the final fourth of the novel - something an editor should have caught. The rest of the novel is pristine and error free, but those name mix-ups are jarring.

Overall, it is a decent read, but I probably won't revisit it. Portia is a very real character, even if she isn't always relatable or likable. The romance is cute and understated; a simple factor in Portia's journey to self-acceptance - something she desperately needs.

6.5/10